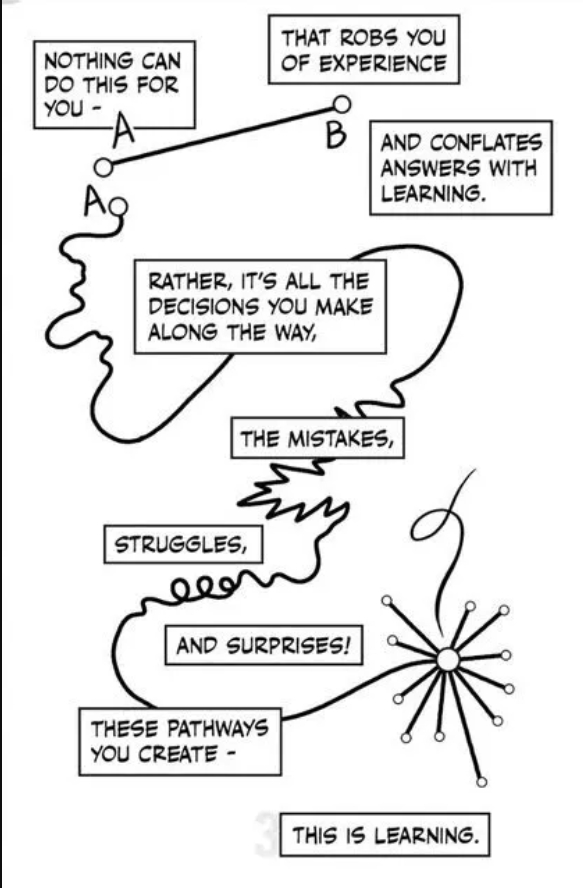

Here comes the AI post related to teaching, building on the first one a few weeks back. In the meantime, I had some nice conversations with some of you on AI, and some more insights related to students and their ways of dealing with it. Reminder, I think that a) AI is overrated vis-à-vis human intelligence, and b) it is REALLY important that we human brains & bodies continue doing the work of thinking, lest our thinking muscles atrophy. Thinking requires time, error, friction – it is a process first, and an outcome second.

With that, let me pivot to the core area of my life where AI plays a role – teaching. Smart AI experts will tell you that “100% of students use it”. See for example, Bowen and Watson (2024), Teaching with AI. A practical guide to a new era of human learning, page 4 (in the first edition – just noticing that there is already a second one). That is not true based on what students tell me (I am assuming here that it would be hard for them to lie in my face). But of course, many students do use it.

What should we professors do about it? Interestingly, this is one of the few areas where our institutions have given us extremely vague guidelines, some would even say: freedom, which, as you may recall, is under threat in many other ways. Everything is in the discretion of the professor; increasingly, we are offered workshops on how to integrate and benefit from AI in teaching. But it really feels more like the administration thinks this is a problem faculty should figure out in the classroom, and they are watching (I would predict they get more proactive once the possibility of a lawsuit enters the picture). Indeed, I have had several conversations with colleagues – we are all somehow, and un-coordinated ways, dealing with this which must be confusing for students, to say the least.

So, a plurality of measures has been developed by thousands of college professors. Personally, I was pleased to see that the straightforward approach of “my teaching is now based on AI” has not been favorably received by students. In at least one case at Northeastern University, they thought they deserved more for their hefty tuition.

My own approach is limited, but has evolved, and in a way that I increasingly enjoy. I started with treating AI pretty much like plagiarism – you cannot steal work (plagiarism); you can also not have a machine produce your work for you. In other words, YOU should do YOUR work. How to deal with this exactly? Our online course management system has both a plagiarism and AI checker, so I can produce reports if either appears in a student’s submission. Because the AI detection is not 100% reliable, I send the report to the student with a reduced grade (say: 60% of the text seems to be AI generated, grade of 10 points is reduced to 4) and ask them to come see me and tell me their story. I then ask them questions like: Did you use AI or did you write this yourself? If self-written, how did you write it? Any thoughts why the AI detection flagged this section of the text? And so forth. At the end of this process, if a student tells me they did NOT use AI and I find this plausible, I change the grade. In other words, the AI detector is not treated as ultimate authority; only if the student does not come talk to me (which happens a lot).

These encounters with students have been eye-opening to me in several ways. First, more students come to see me, and I welcome the fact that this policy creates a new incentive for conversation; we often talk about other things as well. Second, several students have admitted openly using AI. They did it because of time pressure or other chaos in their lives that prevented them from completing the assignment properly. These students are honest, profoundly sorry, and often among the best students in class. I see them take responsibility for a mistake, and many of them vow to not ever do this again. I usually give them a second chance. After all, these students have a very clear understanding of what they are supposed to do.

Third, some students come in and are surprised, shocked and even ashamed that their work should contain AI use. They say they would never cheat and take pride in their work. We then try to find out what happened in the flagged text passages. Some say they use Grammarly to “clean up their language”. Supposedly, according to the detection tools, using this program should NOT be flagged, but apparently, the boundaries between all these programs are getting blurrier by the day. For many of my students, English is not their first language. And even those for whom English is the first language use it. I often suggest not using Grammarly for their next submission to see what happens. And I tell them that it would be good for them to improve their writing independently, without relying on a program (as we had to do in the olden days when Grammarly did not exist – this usually earns me some confused looks).

Fourth, there are students who say things that I first don’t fully understand. As the conversation goes on, I realize that they have a completely different idea about what “writing” and “doing research” means. One student told me they did not use AI, only for structuring the essay. Ok, that is AI use. But why does the student think it is not? So I keep asking, and I hear things like: “I only ask xxx for the outline, and then I fill it in.” Fill it in with what exactly? And how is “structuring the essay” not part of the writing process? Again, my advice: try the next one without using AI.

In another case, the student says they did not use AI but then mused that perhaps in the sections where they summarized literature AI use came up because they translated that summary from Spanish into English. I ask: how did you translate it? Of course, the translation was done by google, not by the student. I suggest that this meant they did not translate it, but had it done by a program; I explain that translation, done by humans, is complex work and that we have a program at the university to become a translator/ interpreter. The student did not know that and became really interested in checking out the program.

Relatedly, I also realized that “summarizing literature” to some of my students does not mean what it means for me, namely “reading it (if not in its entirety, then cursorily), taking notes, and then writing summarizing sentences about it”. Instead, they use summaries already written about that literature they can find online, copy and paste it, and then edit it. The notion of “writing in your own words” which I use in abundance in my syllabi and assignment prompts, that in my own college days really meant to sit down with paper and pen and do that – has, if not evaporated, profoundly transformed. Here, I nostalgically recall my final MA exams, handwritten, over 6 hours. What an achievement that felt to be.

Bottom line: I think it is true that for kids, teens and people in their 20s, there is very little separation of life on- and offline. They do almost all their writing for college through internet-connected computers and phones. What are their own ideas in this context and what are others’? They have a thought, check something real quick, include it in what they are writing, and why should they not have a chat with a chatbot on this, who will probably be helpful in the process? Many of us college professors also realize another parallel: what AI checkers detect as AI produced – generic writing, repetitive sentence structure, certain word choices, etc. – is EXACTLY how many of our real life, blood and flesh, students WRITE. And why is that? Probably because their lives take place in the same spaces where Large Language Models are being trained. The interconnectedness is undeniable.

I assign AI use in limited ways and to create a learning moment (for example: think about topics you want to write your research paper about; write three choices down; then ask AI for paper topics; then make a final choice and reflect on this process). So far, I can say that these reflective engagements with AI have helped me understand my students better, and I think they have clarified some things for them in a very uncertain space. Further, I have seen that MANY students have a clear understanding of authorship and their own creativity and intelligence. For example, some wrote in their reflections they “don’t trust” AI or prefer to come up with their own ideas because they find them more interesting. I feel energized by such answers and commit to supporting these young minds in their unique intellectual development.

To conclude, let me share one interesting chatbot answer. In a class on Postcolonialism, I asked students to answer the question why they did not speak Miccosukee (the language of one Native American tribe in South Florida). It was a surprising question to them, because the Miccosukee language community is very small; accordingly, many answered that they did not know anybody speaking it, that it was not taught in school, and that while they knew about the Miccosukee, they also knew that US history is based on erasure of indigenous peoples. In class, we expanded on the discussion re: colonial erasure. Here, I am sharing parts of the answer I got from ChatGPT to this question:

“That’s a thoughtful question! I don’t speak the Miccosukee language primarily because: … My language abilities are based on the data I was trained on, and Miccosukee is an endangered language with limited publicly available resources … Indigenous languages like Miccosukee are often preserved by the community through oral tradition and selective teaching. That means the language may not be widely published or digitized—both of which are necessary for me to learn from. … Some Indigenous communities … view their languages as sacred or culturally sensitive. Not all of them want AI models or outsiders to access or replicate it, and that choice deserves respect.”

An ”honest” answer in terms of recognizing the limitation of LLMs. AI “knows” that it knows nothing beyond the universe of truths and falsehoods the internet has become. Great answer, ChatGPT! As for us humans, let’s continue to cast the net of learning wider than that.