May is the month in which many countries officially celebrate mothers, so let me talk a bit about motherhood as a commonsense feminist. I have my own experiences to draw on, both as a mom and as a child who was exceptionally well mothered, long into adulthood. But there is so much more – mothering is a social institution, very differently defined throughout history and in different parts of the world. Two characteristics motherhood often comes with, cross-culturally, are a) it works as a social glue and b) it is blatantly devalued.

Throughout my upbringing, I have not perceived the message that motherhood and feminism go well together. Aren’t mothers self-sacrificing, caring creatures, and don’t feminists hate them for that (as they hate so many other stuff, like – MEN)? The idea that real women don’t only accept but embrace their natural calling of motherhood has never gone away, and it seems to be getting stronger recently. Feminism has very critically dissected this narrative. The result is a more realistic understanding of mothering. This helps to put mothering in its right place, which is at society’s core, and it also helps to understand the magnitude of the task, performed by individuals through a lifetime. I am grateful for this feminist learning process. As having children or not is truly the most important decision you will make in your life, I say think it over carefully. And then, go with the flow, either way.

For me personally, May is also the month when my mother passed away (13 years ago now). And this year, May is exceptionally exciting, because my daughter is graduating from high school. In the fall, she will leave her home to go to college in New York City! It feels like I have done the biggest chunk of my job as a mom, but I know there is MUCH more to come.

I read once that a female baby is born with all her eggs already inside her ovaries (millions of them). This means the eggs that will become the children of this female baby exist when she is an embryo – suggesting a very long biological connection between mother and child. In my case, I was not just born in 1968, but existed in egg form already in 1937, and within my maternal grandmother … I found this a crazy thought. I don’t want to get too biological, especially as I believe that non-biological parents can be exactly as caring and bonding as biological ones. But I am interested in the bond that is being created through the social practice of mothering. And when I say mothering, I mean all parenting, but since mothers still do most of it, I keep the term gender specific.

My mom was not a feminist – she would not feel offended by me saying this because she was incredulous when I turned into one. Her life was all about fitting in, doing what was expected of her, caring for others and not being a burden. And being part of a group (family, tennis club) and having some fun. I remember her as a systematic provider, as someone who constantly thought of what others might need that she could do for them. I teach about these things now in my feminist classes calling it “reproductive labor”, but I was not sensitive to any of this when growing up – she was the support structure the entire family took for granted. She was not someone who constantly reminded us of all that she did for us, but even she could get bitterly disappointed when we could not come up with anything thoughtful for Mother’s Day. Or her birthday. Very pathetic on our end, the shame eternally memorable, but what did we change? Not much.

She was good at doing things for others because she had experience in it. There were the daily things like grocery shopping, home cooking, the laundry, but also more extraordinary caring. When I spent some months in Chile for my master’s thesis and found myself in a depressed mood, she called me regularly, at 3 am her morning because of the time difference, to check in on me. When I was in the final stretches of writing my master’s thesis, she took the train from Nuremberg (where she lived) to Hamburg (where I lived), stayed for a week, and made sure I could fully concentrate on putting it all together. She cooked real meals for me (what a luxury in those student days) and proofread everything. She also found the content interesting (on women’s organizations in the Chilean democratization process) and asked at some point: “Was ist denn gender?”

If I am honest, I think much of my development as a human being and finally an academic was about having a life different from hers. A life less hidden, more about standing out, more interesting, and definitely not a life where my raison d’etre is the wellbeing of others. For a long time, I also had no desire to become a mother. However, this was not only because I knew how labor intensive it would be, but also because there was no stable partner in sight and academia did not appear a cozy place for this life project. Still doesn’t. From my mom’s perspective, I had my priorities wrong. Where was the stability, both professionally and in terms of a partnership, why was I moving so much, and why did I need to try everything and could never decide what I really wanted? I took me a while to understand that she had not just subordinated her needs but made decisions in her life and stood by them, accepting the good and the bad parts.

When I became a mom (a single mom at first), I emulated many of her practices. In my brainy life, I had no idea about the diapers, the bathing, the feeding, the teething, and the constant demands of a baby, the impossibility of having five minutes for yourself (that was the hardest after the academic normal of reading and writing for hours). She had her little tricks – I don’t remember many, but they helped a lot (here is one: cut baby fingernails when the baby is asleep). I also, finally, realized how much I had benefitted from her constant care work, and how non-natural it is to do this work. As other parents, I have experienced it as a great joy to raise my child, but especially throughout the early years, I think I was a completely different person out of pure exhaustion.

So where is the feminism in the mothering? One dimension is recognizing the concrete (for the kid) and general (for the world) importance of care work. It is embarrassing to say that I only fully understood the value of care work when I had to do it myself. That is when one also understands its devaluation. And perhaps, people who never do it, or do very little of it, never understand it. After initial single parenting, I have long lived in a partnership where we share reproductive labor, more or less equally. Perhaps our daughter learns something from seeing this.

Another dimension is that in the concrete relationship that mothering is, one can make room for values such as justice, self-love, equality, solidarity, kindness, and respect. The good things humanity needs and never has enough of. The dinner table is a good place for that, or the reading stories at bedtime. I would have liked to be more involved in my daughter’s schooling, but it did not work out for me as a working mom, with a few exceptions. In elementary school, she and I did a human rights-inspired puppet play for her class. That was a highlight, because we also made the puppets ourselves, and I think the kids liked the change of pace.

Other than that, I distinguished myself mostly in writing letters to teachers or principals if I was unhappy with something that had happened in school. To spare my daughter embarrassment, I will only mention my intervention in kindergarten when the kids started to do the pledge of allegiance without knowing what it meant. The teacher did not deny that but found no fault in it. She offered: “She does not have to do it if she does not want to”. In a room of five-year-olds and the teacher doing it. There were several occasions when my daughter explicitly rejected me sending a letter I had already written – this was not a practice that she recognized from other parents, and it was awkward, even embarrassing. However, I think she understood there is value in speaking up about a matter that one feels strongly about. And more basic, that sometimes it is preferable not to go with the flow, even if it might feel scary. Because accepting a problematic status quo could be even scarier.

I think of mothering as something that is a strong, passionate, and socially fundamental way of being. I found it also hard, especially when I did not quite know what to do. In the motherhood-is-natural-narrative, there is no place for this as you are supposed to know instinctively what to do. I often did not. And I found myself surprisingly unhelpful in my daughter’s teenage years – the world as it opens to her is so different from the one that opened to me. How useful can my guidance be?

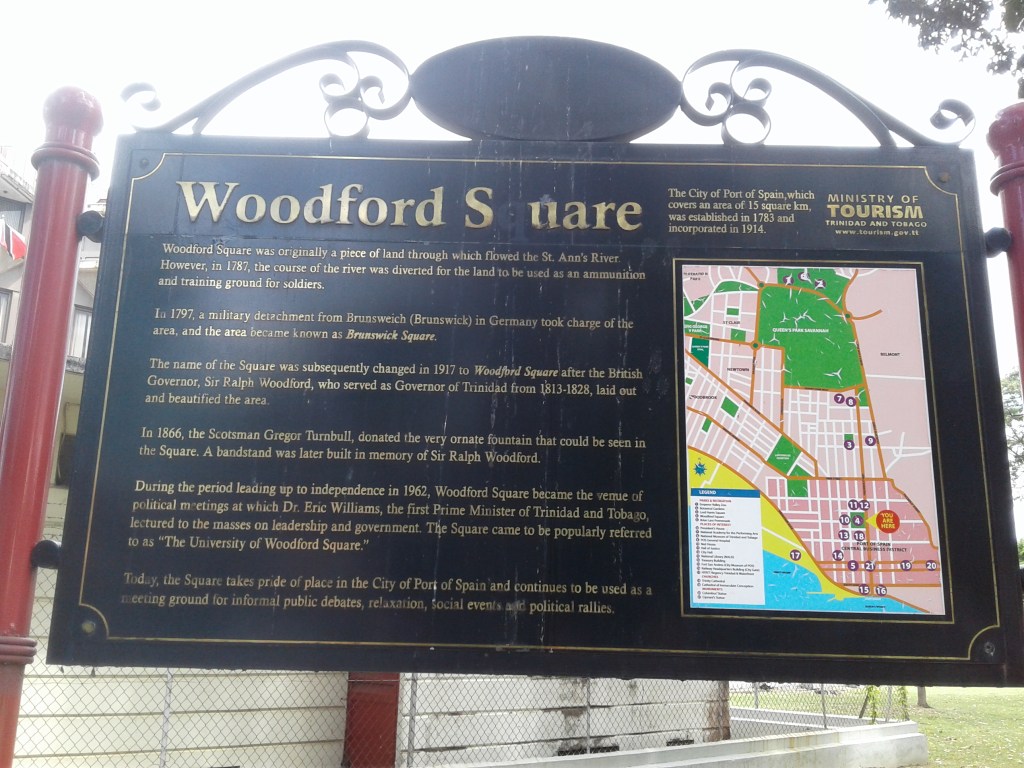

All things considered: in my experience, feminism and motherhood work well together. It helps creating self-respecting, caring children. But I realize my experience and that of the mothering friends around me is a privileged one. We never lived in poverty, our mothering abilities were never questioned because of race or social status, our children were never taken from us, we had access to decent schooling and healthcare. Other mothers are up against much more adversities and some of them organize collectively to fight them. Most heroic in this sense remain the mothers’ and grandmothers’ organizations under Latin American military dictatorships in the 1970s and 80s. These organizations were created by mothers who looked for their disappeared children, and their brave public demands to get them back, or one could say, their public mothering, destabilized the military regimes. They did not get what they most wanted – their children alive – but they did not stop.

There are other mothers’ organizations who politicize their supposedly private roles for a public cause. In the United States, one of them is Moms Demand Action for gun sense in America. Another one to which I donate annually for Mother’s Day, is The National Bail Out Collective. This organization works to get mothers and care givers out of pre-trial detention where they end up because they cannot afford bail. This means they are imprisoned – losing their homes, jobs, and custody of their children – not because they are convicted of a crime, but because they are poor. And mostly black. Perhaps you want to join this organization’s efforts. Every year a few weeks after mothers’ day I get an email that specifies how many mothers were bailed out. It is a small victory in an inhumane incarceration system, but it is gratifying.